As part of the Academic Integrity in STEMM module I teach at Imperial College London, I introduce undergraduate students from a variety of disciplines to current ideas in academic integrity research. This year, I presented a session on artificial intelligence to them for the first time. This is a subject for which the educational implications are still only just being explored at a high level. The session was also developed to help students to think about research topics they could themselves investigate, so although there is little research peer reviewed research published to date on academic integrity and artificial intelligence, the session was framed to allow research questions to be considered and research ideas to be explored.

During the session, I demonstrated how I had been able to automatically transcribe some of my teaching materials, then run the transcript through the GPT-3 Playground and produce a useful summary of the main talking points. I can’t share the lecture I gave the students directly, not least because many of them contributed their own opinions and ideas. I can say that I expect that many of the same concepts will be reiterated in upcoming talks and keynote addresses I’m giving on this subject. What I can share is some of the high-level ideas we discussed as a group. I used GPT-3 again to help me to organise my thoughts for this post from the transcript, although very little of the GPT-3 generated text remains in this blog post.

Should We Just Ban AI In Education?

To start with, we considered if using AI tools should be considered for use at all in an educational setting. Their use can be controversial as the technology can be used to breach academic integrity. Of course, the question is not one with a simple yes or no answer. Many students identified where AI was already being used within their own degree and was not considered a new or controversial subject. The answer about what is acceptable will depend very much on the type of AI, how it is being used and the subject being studied. It is the misuse of AI that is the problem, not the use of AI, although that still leaves a question regarding how misuse can be best defined.

We discussed how students were already using AI outside the official parameters of their course, with tools like ChatGPT being useful to help them to understand concepts, in the same way that other students might look for YouTube videos (or students of a previous generation might have read textbooks). I mentioned how I had seen my own students in class using on ChatGPT, but not in a way that appeared to be breaching academic integrity. This brought with it another potential challenge, as students have to be taught how to critically evaluate the reliability of AI generated answers, especially at a more advanced level, and realise that they cannot rely solely on the generated text. I noted that the jury is still out as to how accurate AI generated answers are and that more research and evidence was needed to address this question. It has been regularly demonstrated, for example, that ChatGPT can give very wrong answers to mathematical questions and can invent quotes and references.

As an example, we talked about how AI is already being used in the medical field. Doctors can access published medical findings that may be applicable to only a small number of people worldwide and which they would be unlikely to ever discover by hand. But they need to understand how and why results have been returned, rather than relying on a machine made decision for a diagnosis. AI can give wrong answers. AI text generators can make up sentences that some people would perceive as facts. A patient who attempts to self-diagnose using GPT-3 type technologies may be misled or may have dangerous ideas which are far from the truth. Therefore understand AI technology, what this means in practice, and how to work with this, must be an essential skill that will be needed for Doctors of the future. Similar arguments could made for many other fields.

Do Students Know Understand AI?

Underlying all of the questions is the need for students, and others, to understand what AI really means. Intelligence is really the wrong word. I explained that machine learning is just a set of numbers and statistics. I described how ChatGPT worked at a very high level and how the tool generates responses based on properties of the data it has been trained on, essentially mimicking a structure rather than understanding the meaning behind the words it generated. I also talked about how the current systems aimed at end users are really just an extension of the automatic rewriting systems that have been around for many years, often used to help disguise documents to that they are not perceived as being plagiarised. These same techniques have been used in the commercial world by people looking to steal content for their websites, allowing them to get traffic and visitors, but without needing to write fresh articles for text.

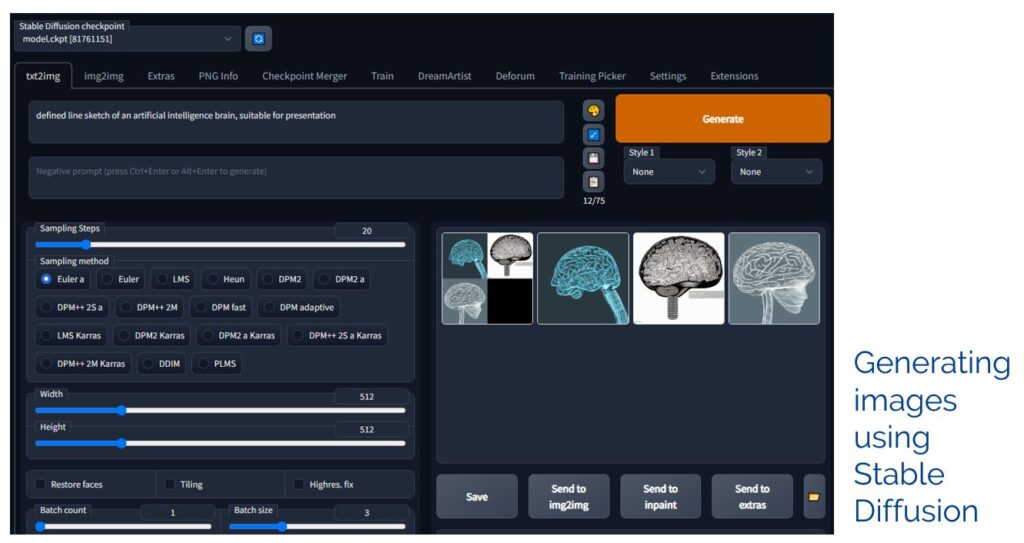

I also discussed how much of the wider discussion of AI misuse in education relates solely to text and essays, but many other types of assessed elements can be generated. Some examples include using ChatGPT to generate LaTeX test, which can be compiled for presentations, writing computer programs, as well as interfacing with models like Stable Diffusion to generate graphics (and I share other examples in this post). Some of these systems can even be run locally and do not require an Internet connection or sharing your data and ideas with a third party. As I said to the students, I use generated images myself to enhance talks and lectures, but this isn’t done in a way that is intended to deceive anyone.

Ignoring and Banning

I wrapped much of the session up around a simple model with four options, all of which I’ve observed across the higher education sector at different times. I call the options: ignore, embrace, ban, and educate.

I argued that ignoring ChatGPT and AI was just not a consideration. There is not much formal research on AI and academic integrity yet, but I did show some results of a survey of 1000 students over the age of 18, which had been shared by a commercial company. The survey suggested that many participants had already used ChatGPT to help with homework and assignments. However, looking at the results of the survey within the context of the module and from a research perspective, there were many indications that the results were not fully reliable and that subtleties as to how the survey was conducted and exactly who completed it were not clear. Nevertheless, many would interpret the results as saying that students were admitting using ChatGPT to cheat. If students know about and are using ChatGPT, for good or bad, this is not something that cannot be ignored.

Some people are advocating for a ban on ChatGPT, with some school districts already having blocked ChatGPT from their networks. This is simply unworkable. Students have mobile phones and can access this technology in many other ways and that is before it starts being widely available integrated into search engines and the like.

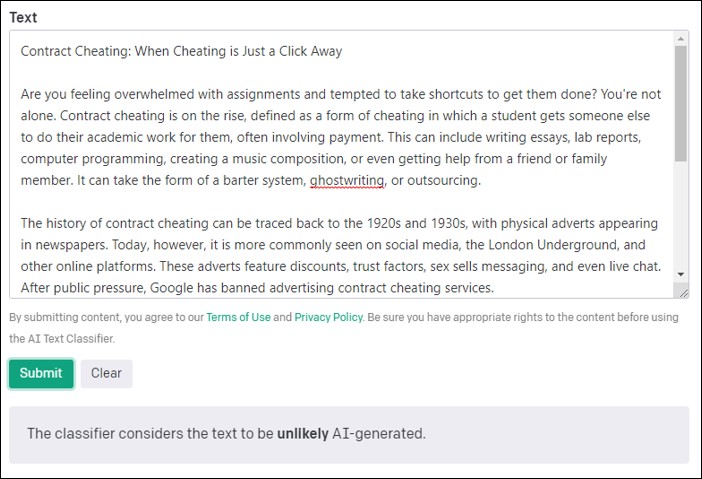

Many edtech companies have themselves jumped on the idea that AI generated text should be banned, or at least they have jumped on the commercial opportunities that attempting to enforce such a ban will offer them. I stated that around ten new systems claiming to detect AI-generated text had been released in January 2023. However, my belief is that the current AI detection system was not reliable and that it would be dangerous for universities to rely on these to penalise or accuse students.

Just as not everyone understands how AI generated text is produced, nor do they understand how the current batch of AI detection systems work, or what the numbers they give actually mean. Systems like GPTZero have been highlighted in the media as a rapid response to AI generated text due to clever marketing and carefully constructed success figures that are written in such a way that they can be easily misinterpreted. The current generation of AI generation systems do not usually publish their code or models and are essentially a black box, totally unverifiable, essentially a machine learning approach that relies on being provided by examples of text written by humans and by machines, then attempts to identify properties that differentiate between the two groups. However, some of these systems only claim to give a correct classification just over 50% of the time, barely better than a random guess. Until AI detection systems can start to provide human understandable reasons why they are making those decisions, the results cannot be relied on.

There’s also a need for independent and systematic testing of these AI detection systems to carried out. As an example, I showed an blog post (unpublished) that I’d generated based on a transcript of a previous talk I’d given to the students on contract cheating. The talk was completely my own work, but the blog post summary was machine generated, so should show all the properties of AI writing. As it happened, this was not the case. Running this through the AI writing detector developed by OpenAI (the same company who wrote the software used to generate the post) showed this as 100% original. Universities do set blog post writing activities as assignment tasks and many would already argue against the suitability of a traditional essay as a form of assessment, so any AI detection technology that does not consider this type of assessment is arguably not fit for purpose. Putting this aside, exactly how a blog post which is the combined work of a human and a machine should be classified by an AI detector is an open question that has not yet been properly considered.

Educating and Embracing

Although some caution towards AI is merited, it appears that ignoring and banning are both unworkable options. Educating students about AI and embracing emerging technology is more appropriate. How that looks may well be discipline dependent and local levels of recommendation may need to be developed.

It can be argued that AI can help students to learn, with more personalised instruction and support being available for them. If students all have access to the same AI technology, this may also reduce the opportunity for them to cheat and the reasons why cheating may be necessary. But setting assignments that rely on particular AI tools can be dangerous. For example, at present, I would not recommend setting assessed tasks that depend solely on ChatGPT. There are no guarantees that this tool will be available at any given time. There are also no guarantees that this will be provided free of charge and it is unfair to expect students to pay for access. This may simply introduce more issues of inequality.

It may also be appropriate to consider if some of the current AI detection tools can be used instead as tools to help students to develop as academic writers and to avoid them becoming over-reliant on technology. Many of the AI detection tools seem largely to be looking for good academic writing and use imperfections to suggest that work has been written by a human. Of course, the argument about when it is acceptable to use AI technologies to generate text during an assessment process is still one for which there is not a single consistent agreed answer. Even if this is embraced, it may still be necessary to verify that students know how to write unaided in some situations and how to write with machine support in other situations.

Unsurprisingly, many of the ideas in the lecture overlap with those in the briefing paper by the UK Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) on the artificial intelligence threat to academic integrity, one of the first briefings of its kind released to the sector. The overlap is unsurprising, as I contributed to the briefing paper as part of my role on the QAA Academic Integrity Advisory Group. I emphasised again the importance of communicating with students about what AI can and can’t do, promoting academic integrity as a consideration central to all of education, and being careful about detection. I also encouraged the students to go away and experiment with AI tools to understand them better, including those specific to their own disciplines, but also to be cautious about misuse.

As I said to the students, researching AI in education is a hot topic, with many opportunities for exploration and discovery, as well as to follow in the footsteps of the student who created GPTZero and to get media publicity if they so desire.. I encouraged students to think about this in relation to their own research projects, but to take care with research design as the field is moving so fast. I look forward to seeing what the students come up with, whether this relates to academic integrity and artificial intelligence, or to any other aspect of interest to the academic integrity community.

Thomas- I think it is so crucial to discuss AI with students as you have done here. In my experience anyone who thinks seriously about the technology is coming to a consensus that is very like what is here. The higher education system, notwithstanding balanced briefings from the likes of QAA, TEQSA and EUA, is still pretty much in denial mode and HE leadership needs to be educated. Students could tell them a thing or two!

“It’s the misuse of AI that is the problem, not the AI itself.” Wow, that really stuck with me. Nothing more true than that observation, Thomas. We have all seen this trend in emerging technologies that organizations and governments ban them, hoping it would disappear. To me, Generative AI looks like a revolution in all spheres of knowledge and one that is fast approaching. The work on academic integrity that you are doing is inspiring to me and serves as the beginning of that revolution in academia. Thank you for sharing the article and I’d love to hear your thoughts on the use of Generative AI is sensitive areas such as Therapy so please feel free to reach out to me because I am developing a startup in that field and your expertise would be a blessing.